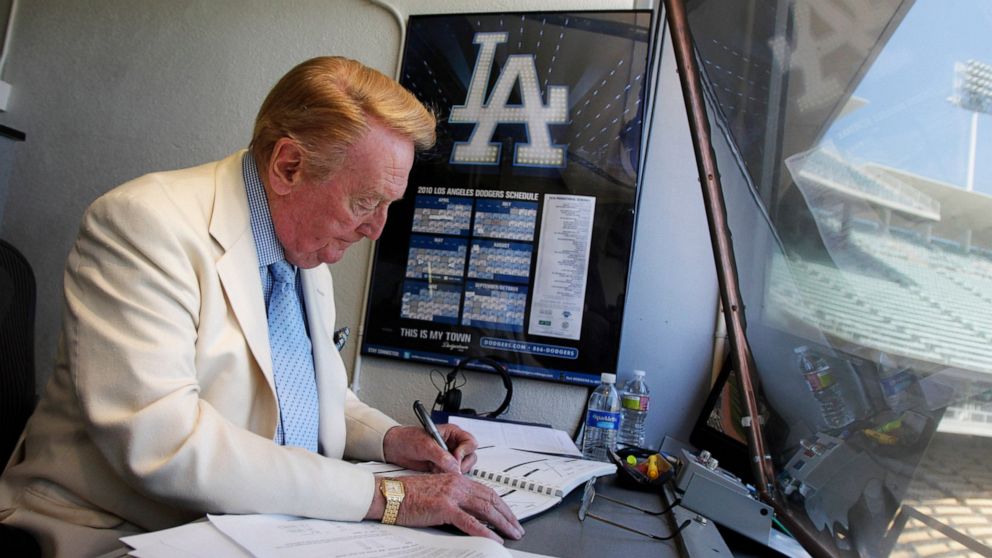

LOS ANGELES -- Hall of Fame broadcaster Vin Scully, whose dulcet tones provided the soundtrack of summer while entertaining and informing Dodgers fans in Brooklyn and Los Angeles for 67 years, died Tuesday night. He was 94.

Scully died at his home in the Hidden Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles, according to the team after being informed by family members. No cause of death was provided.

“He was the best there ever was,” pitcher Clayton Kershaw said after the Dodgers game in San Francisco. “Just such a special man. I’m grateful and thankful I got to know him as well as I did.”

As the longest tenured broadcaster with a single team in pro sports history, Scully saw it all and called it all. He began in the 1950s era of Pee Wee Reese and Jackie Robinson, on to the 1960s with Don Drysdale and Sandy Koufax, into the 1970s with Steve Garvey and Don Sutton, and through the 1980s with Orel Hershiser and Fernando Valenzuela. In the 1990s, it was Mike Piazza and Hideo Nomo, followed by Kershaw, Manny Ramirez and Yasiel Puig in the 21st century.

“You gave me my Wild Horse name. You gave me love. You hugged me like a father,” tweeted Puig, the talented Cuban-born outfielder who burned brightly upon his Dodgers debut in 2013. “I will never forget you, my heart is broken.”

The Dodgers changed players, managers, executives, owners — and even coasts — but Scully and his soothing, insightful style remained a constant for the fans.

He opened broadcasts with the familiar greeting, “Hi, everybody, and a very pleasant good evening to you wherever you may be.”

Ever gracious both in person and on the air, Scully considered himself merely a conduit between the game and the fans.

After the Dodgers' 9-5 win, the Giants posted a Scully tribute on the videoboard.

"There’s not a better storyteller and I think everyone considers him family,” Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said. “He was in our living rooms for many generations. He lived a fantastic life, a legacy that will live on forever.”

Although he was paid by the Dodgers, Scully was unafraid to criticize a bad play or a manager’s decision, or praise an opponent while spinning stories against a backdrop of routine plays and noteworthy achievements. He always said he wanted to see things with his eyes, not his heart.

“We have lost an icon," team president and CEO Stan Kasten said. "His voice will always be heard and etched in all of our minds forever.”

Vincent Edward Scully was born Nov. 29, 1927, in the Bronx. He was the son of a silk salesman who died of pneumonia when Scully was 7. His mother moved the family to Brooklyn, where the red-haired, blue-eyed Scully grew up playing stickball in the streets.

As a child, Scully would grab a pillow, put it under the family’s four-legged radio and lay his head directly under the speaker to hear whatever college football game was on the air. With a snack of saltine crackers and a glass of milk nearby, the boy was transfixed by the crowd’s roar that raised goosebumps. He thought he’d like to call the action himself.

Scully, who played outfield for two years on the Fordham University baseball team, began his career by working baseball, football and basketball games for the university’s radio station.

At age 22, he was hired by a CBS radio affiliate in Washington, D.C.

He soon joined Hall of Famer Red Barber and Connie Desmond in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ radio and television booths. In 1953, at age 25, Scully became the youngest person to broadcast a World Series game, a mark that still stands.

He moved west with the Dodgers in 1958. Scully called three perfect games — Don Larsen in the 1956 World Series, Sandy Koufax in 1965 and Dennis Martinez in 1991 — and 18 no-hitters.

He also was on the air when Don Drysdale set his scoreless innings streak of 58 2/3 innings in 1968 and again when Hershiser broke the record with 59 consecutive scoreless innings 20 years later.

When Hank Aaron hit his 715th home run to break Babe Ruth’s record in 1974, it was against the Dodgers and, of course, Scully called it.

“A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol,” Scully told listeners. “What a marvelous moment for baseball.”

Scully credited the birth of the transistor radio as “the greatest single break” of his career. Fans had trouble recognizing the lesser players during the Dodgers’ first four years in the vast Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

“They were 70 or so odd rows away from the action,” he said in 2016. “They brought the radio to find out about all the other players and to see what they were trying to see down on the field.”

That habit carried over when the team moved to Dodger Stadium in 1962. Fans held radios to their ears, and those not present listened from home or the car, allowing Scully to connect generations of families with his words.

He often said it was best to describe a big play quickly and then be quiet so fans could listen to the pandemonium. After Koufax’s perfect game in 1965, Scully went silent for 38 seconds before talking again. He was similarly silent for a time after Kirk Gibson’s pinch-hit home run to win Game 1 of the 1988 World Series.

He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame that year, and also had the stadium’s press box named for him in 2001. The street leading to Dodger Stadium’s main gate was named in his honor in 2016.

That same year he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama.

“God has been so good to me to allow me to do what I’m doing,” Scully, a devout Catholic who attended mass on Sundays before heading to the ballpark, said before retiring. “A childhood dream that came to pass and then giving me 67 years to enjoy every minute of it. That’s a pretty large thanksgiving day for me.”

In addition to being the voice of the Dodgers, Scully called play-by-play for NFL games and PGA Tour events as well as calling 25 World Series and 12 All-Star Games. He was NBC’s lead baseball announcer from 1983-89.

While being one of the most widely heard broadcasters in the nation, Scully was an intensely private man. Once the baseball season ended, he would disappear. He rarely did personal appearances or sports talk shows. He preferred spending time with his family.

In 1972, his first wife, Joan, died of an accidental overdose of medicine. He was left with three young children. Two years later, he met the woman who would become his second wife, Sandra, a secretary for the NFL’s Los Angeles Rams. She had two young children from a previous marriage, and they combined their families into what Scully once called “my own Brady Bunch.”

He said he realized time was the most precious thing in the world and that he wanted to use his time to spend with his loved ones. In the early 1960s, Scully quit smoking with the help of his family. In the shirt pocket where he kept a pack of cigarettes, Scully stuck a family photo. Whenever he felt like he needed a smoke, he pulled out the photo to remind him why he quit. Eight months later, Scully never smoked again.

After retiring in 2016, Scully made just a handful of appearances at Dodger Stadium and his sweet voice was heard narrating an occasional video played during games. Mostly, he was content to stay close to home.

“I just want to be remembered as a good man, an honest man, and one who lived up to his own beliefs,” he said in 2016.

In 2020, Scully auctioned off years of his personal memorabilia, which raised over $2 million. A portion of it was donated to UCLA for ALS research.

He was preceded in death by his second wife, Sandra. She died of complications of ALS at age 76 in 2021. The couple, who were married 47 years, had daughter Catherine together.

Scully’s other children are Kelly, Erin, Todd and Kevin. A son, Michael, died in a helicopter crash in 1994.

———

Former Associated Press staffer Stan Miller contributed biographical information to this report.

———

More AP MLB: https://apnews.com/hub/MLB and https://twitter.com/AP—Sport

Source https://www.globalcourant.com/vin-scully-dodgers-broadcaster-for-67-years-dies-at-94/?feed_id=5916&_unique_id=62ea113823546